Hillcrest is a suburban area located in southeast Washington DC, 3 miles from the Capitol in Ward 7. As indicated in the name, the neighborhood is at a higher altitude than the majority of the District, resting at 300 feet above sea level and remains a relatively forested area. Hillcrest is contained within the borders of Pennsylvania Avenue SE, Southern Avenue, Naylor Road, and 28th Street SE, as cited by the Hillcrest Community Civic Association.

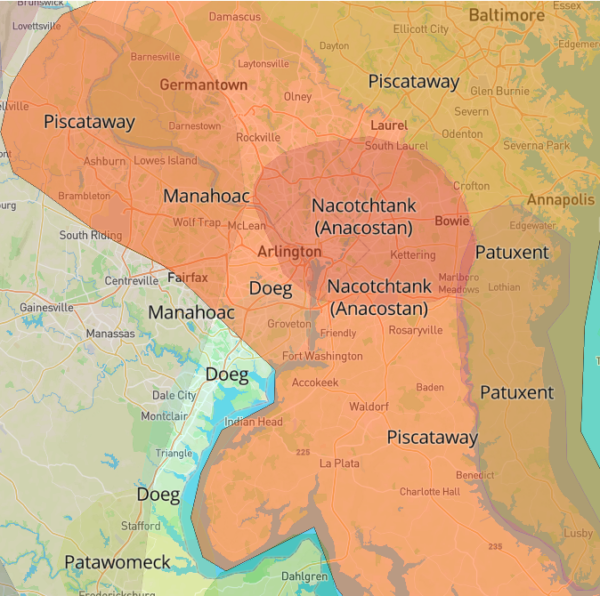

Now a site for the single-family homes for upper-middle-class Washingtonians, this land — like much of the District and surrounding area — belonged to Native Americans, specifically the Piscataway people. The Piscataway were more agrarian than some of their fellow Algonquian-speaking neighbors, which led them to establish permanent villages — which the English often used to denote specific groups. Hillcrest resides on what was once Nacotchtank tribal land, the largest of three villages, alongside the southeast of the Anacostia River (Eastern Branch of the Potomac River). The English referred to this population as the Nacotchtank, or the Latinized alternative Anacostans, after their location.

The people of Nacotchtank were renowned for their status as traders, Nacotchtank itself is a derivative of anaquashatanik, which means “town of traders.” Their position on fertile land near two both the Anacostia and Potomac rivers allowed the people of Nacotchtank to become prolific traders, selling beans, squash, maize, and wild game.

The surge of English colonists into what is now Maryland from the 1650s marked a swift decline in the population of the Nacotchtank-Piscataway peoples. Before this era, there were clashes with European settlers and neighboring rival tribes (Patawomeke), the popularity of tobacco as a cash crop exacerbated these conflicts. In 1663, Thomas Dent was granted an 850-acre plot of land off the Potomac named Gisborough, which bordered Nacotchtank land. Colonists believed they were entitled to the wide expanses of land to create profit through tobacco plantations. As they encroached upon Piscataway lands, the proximity to European settlers devastated the local indigenous population through skirmishes and the exposure to diseases like smallpox, measles, and cholera.

After the removal of the Nacotchtank-Piscataway peoples via war, disease, and dispossession, this general area maintained its rural roots up until the 1900s. Much akin to Woodridge, Hillcrest’s distance from the Capitol meant that it was often inaccessible to most who lived in the central city, particularly those who did not have the financial ability to travel frequently. Because of this, many of Hillcrest’s original residents were members of Congress and white elites. In fact, the developer of Hillcrest, Colonel Arthur E. Randle, moved his family into a grand Greek Revival house, later given the moniker “The Southeast White House” to encourage others to build lavish homes along Pennsylvania Ave. By the early 1900s, streetcars encouraged the construction of single-family homes, populated by the elite and middle-class white families.

After the 1948 Shelley v. Kramer Supreme Court decision, which outlawed racially restrictive housing covenants, Hillcrest became accessible to middle-to-upper-class African Americans. This was an ample opportunity for young Black families to move out of the crowded heart of the District to homes that were more spacious and affordable.

The increase of African Americans within Hillcrest from 1960 to 1980 directly correlated with the flight of white residents in the area, especially after the uprisings in 1968 following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Though the neighborhood was largely shielded from the turmoil in more dense parts of the city, only 35% of Hillcrest’s white population remained through 1970. As the Black population in Hillcrest grew, it attracted Black professionals such as future Mayor Marion Barry to the neighborhood.

Over time, Hillcrest has remained a more affordable alternative for middle-class and upper-class families within the District.

Hillcrest is often seen as an isolated oasis from the hustle and bustle of the city, and this has been a main promoting point of the community for over a century. After the success of Colonel Randle’s Southeast White House in Congress Heights, politicians in the 1890s saw the potential of the area, buying up 800-acres of the land and selling it to upscale residential development contractors to create East Washington Heights. In the early 1900s, Colonel Randle took over the development planning for most of Washington Heights, establishing Hillcrest and the surrounding communities. In the 1940s and 1950s, advertisements often boasted cooler temperatures than the rest of the District due to its higher altitude (300 feet above sea level).

Hillcrest’s key selling point has been its proximity to the Capitol, without the challenges that come with density. This made Hillcrest perfect for young families to raise their children. These factors led Hillcrest to be highly sought after — especially by Black families after the prohibition of racialized housing practices. The neighborhood was developed to resemble another community in the District called Crestwood, which was known for its Black professionals, opulence, and lavish architecture on 16th Street NW. This enclave of African Americans was called the “Golden Coast,” prospective Hillcrest residents noticed that it had the same charm as Crestwood, and thus the nickname “Silver Coast” became popularized after its use by Ward 7 Councilmember Willie Hardy.

Westover Drive, a street named after the suburban neighborhood in Arlington, Virginia, is the pinnacle of Hillcrest’s real estate value, as it holds an impressive view of Downtown. Its development began in 1937, and its extravagant houses have been home to many of the District’s elite, like H.R. Crawford, Delbert Lee, and Adam Clayton Powell.

Currently, Hillcrest remains a more affordable option for many who want to live in the District, especially those who want nineteenth and twentieth century homes for a lower price than if they would West of the Anacostia River.

The Hillcrest Community Civic Association (HCCA) was established in 1989 by Belva T. Simmons, which is much later than many of its counterparts, like the Woodridge Civic Association that started in 1953. This is due to the steady increase of Black residents in Hillcrest after the establishment of the “Silver Coast,” a refined space that reflected the aesthetics of the “Gold Coast,” which was rife with African American professionals.

When first created, the HCCA strove to advocate for the community at all levels, as Hillcrest was the only neighborhood in Ward 7 without one. The primary goals of the current HCCA are to establish Hillcrest as a model of goodwill, respectfulness, civility, collaboration, and communal support, while being respectful to the environment; preserving old traditions while still being open to new ideals and schools of thought.

For the twentieth anniversary of the Association, Hillcrest journalist and scholar Michelle Phipps-Evans collected the oral histories of longtime residents of varying ages who were involved in the HCCA, so that the community’s culture and history can could be documented across generations. Evans then composed a comprehensive piece that boiled down the central ideas of the interviews, the values of residents, and the qualities that make Hillcrest what it is today. Evans also provided base questions for others to use in the future to inspire future journalists and oral historians, while memorializing the everyday history-makers in their own communities.

Stephanson’s Bakery

Once situated at 23rd and Pennsylvania Ave S.E., Stephanson’s Bakery was a cornerstone of the community. Founded and owned by James G. and Alice M. Stephanson, long-time residents of Hillcrest, kept the bakery within the family from 1928 to 1961! Stephanson’s Bakery sold a multitude of goods but were well known for their pies, which were advertised for 50 cents in 1949. Stephanson’s was not closed because of low sales — quite the contrary, they had lines bustling out the doors most days of the week — but instead due to the expansion of the 295-cloverleaf highway in 1961. Even though the bakery was demolished, the family continued to live in Hillcrest and give back to their community.

Here is Stephanson’s recipe for their Coconut Custard Pie and Butter Tea Cookies for you to try at home!

Here is Stephanson’s recipe for their Coconut Custard Pie and Butter Tea Cookies for you to try at home!

Hillcrest Recreation Center

The Hillcrest Recreation Center, located off Branch Avenue, has been a focal point in the community for decades, hosting local societies, clubs, and activities for all ages. At this point in time, the Recreation Center offers: an arts & craft room, computer lab, fitness center, gymnasium / indoor basketball court, large multi-purpose room, community garden, outdoor fitness equipment, walking trail, pavilion with shade, Play DC playground, and spray park.

Mrs. Euphemia L. Haynes, a Black educator with her bachelor’s, master's, and doctorate degrees, had her invitation to speak to the Pre-School Parents Club withdrawn by a District Recreation Department employee due to her race in 1961. Dr. Haynes was selected by the program chairman, Mrs. Barbara Clark, to talk about the fears of 3- to 4-year-olds because of her accolades — though Clark did not know Dr. Haynes was African American. In fact, Dr. Haynes was the first African American woman to earn a PhD in mathematics, and her husband was previously the Deputy District School Superintendent. The assistant of the Center’s director was the one to withdraw the invitation, but all departments of the Center were desegregated at this point.

Mrs. Euphemia L. Haynes, a Black educator with her bachelor’s, master's, and doctorate degrees, had her invitation to speak to the Pre-School Parents Club withdrawn by a District Recreation Department employee due to her race in 1961. Dr. Haynes was selected by the program chairman, Mrs. Barbara Clark, to talk about the fears of 3- to 4-year-olds because of her accolades — though Clark did not know Dr. Haynes was African American. In fact, Dr. Haynes was the first African American woman to earn a PhD in mathematics, and her husband was previously the Deputy District School Superintendent. The assistant of the Center’s director was the one to withdraw the invitation, but all departments of the Center were desegregated at this point.

In response to this blatant discrimination — though the employee said that the withdrawn invitation would save Dr. Haynes the embarrassment of parents walking out of her lecture — Mrs. Clark and President Cynthia Stoertz resigned from their positions in the parent’s club in protest to Dr. Haynes treatment.

After this transgression, members of the club voted, 38-40, to keep the speakers for the rest of the season as scheduled, regardless of their race. This did not reinstate Dr. Haynes lecture, though she did receive public apologies from District recreation officials.